Meyer awarded competitive Verville Fellowship at Smithsonian

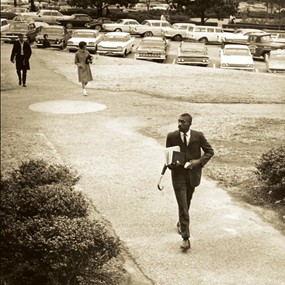

Following a lifetime of interest in aviation, Alan Meyer is currently conducting research surrounding diversity and inclusion within the industry as a Verville Fellow at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The Verville Fellowship is a competitive nine to twelve-month in-residence fellowship intended for the analysis of major trends, developments, and accomplishments in the history of aviation or space studies.

"The Smithsonian only awards one Verville Fellowship each year, and the competition is pretty tough. So it’s a great honor to be selected, and also a huge vote of confidence that my topic matters," Meyer said.

As an associate professor of history, Meyer teaches on the history of technology and aviation history. "Broadly speaking I'm a social and cultural historian of technology, with a narrower focus on aviation history. This means I study how people interact with technology, not just the nuts and bolts of airplanes. I'm particularly interested in how gender, race, and class play out in technology and society," Meyer said.

As a Verville Fellow, Meyer is specifically researching the lack of African American pilots in the industry.

"My first book, Weekend Pilots, examined reasons for the continued low number of women in the cockpit. In the process of my research, I discovered something that pretty much anyone who’s been around aviation for a while can tell you: nonwhite minorities are also underrepresented in the airline cockpit. So after I finished my first book, this seemed like a natural question to tackle: why has it taken so long to integrate the airline cockpit?"

Meyer's research methodology as a Verville Fellow involves three main sources: 1. Examining articles and letters to the editor printed in magazines like Ebony and Jet from the 1950s up to the recent past. 2. The pilots themselves - through autobiographies, obituaries, and oral history interviews, which Meyer is conducting with African American airline pilots ranging from those who started flying in the 1960s right up to the present generation who are just entering the profession. 3. Obtain and analyze historical information compiled by the Census Bureau and other agencies.

“For instance, my own research indicates that 96 percent of the first generation of African American airline pilots—that is, those hired between 1964 and about 1980—had completed at least some college before they were hired, and more than 80 percent had earned a four-year degree. Meanwhile, as of 1980, only half of all African Americans age 25 or older had completed high school, compared to nearly 70 percent of white Americans. And the gap is even larger regarding higher education. That year, only 8.4 percent of African Americans nationwide possessed a four-year college degree, compared to 17 percent of white Americans. So right there we can start to see one of many potential obstacles to becoming an airline pilot,” Meyer said.

According to Meyer, both the airlines and the military—which Meyer said has traditionally trained many of the pilots who eventually end up flying for the airlines—have been trying to increase the diversity of their flight crews for decades.

As a retired member of the Green Berets, Meyer referenced General Charles Q. Brown, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, who recently stated that the number of African American pilots is about the same as when he started flying 30 years ago, which is approximately just two percent.

"Brown was talking about the Air Force. The civilian side is a little better, but not much. In 2000, only 1.7 percent of commercial pilots were African American. Today the figure remains below 3 percent, a far cry from racial parity when African Americans make up more than 13 percent of the nation’s population."

Meyer said that the airlines are predicting a pilot shortage soon, which might contribute to increased diversity among pilots.

"Anytime you’re hiring lots of new folks, that’s when you have an opportunity to change things for the better. But if you want to make effective changes, and not just throw money at the symptoms, you need to understand—and I mean truly understand—the underlying problems that caused those symptoms. And that’s where thoughtful and comprehensive historical research comes in," Meyer said.

Tags: Research Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion History Faculty